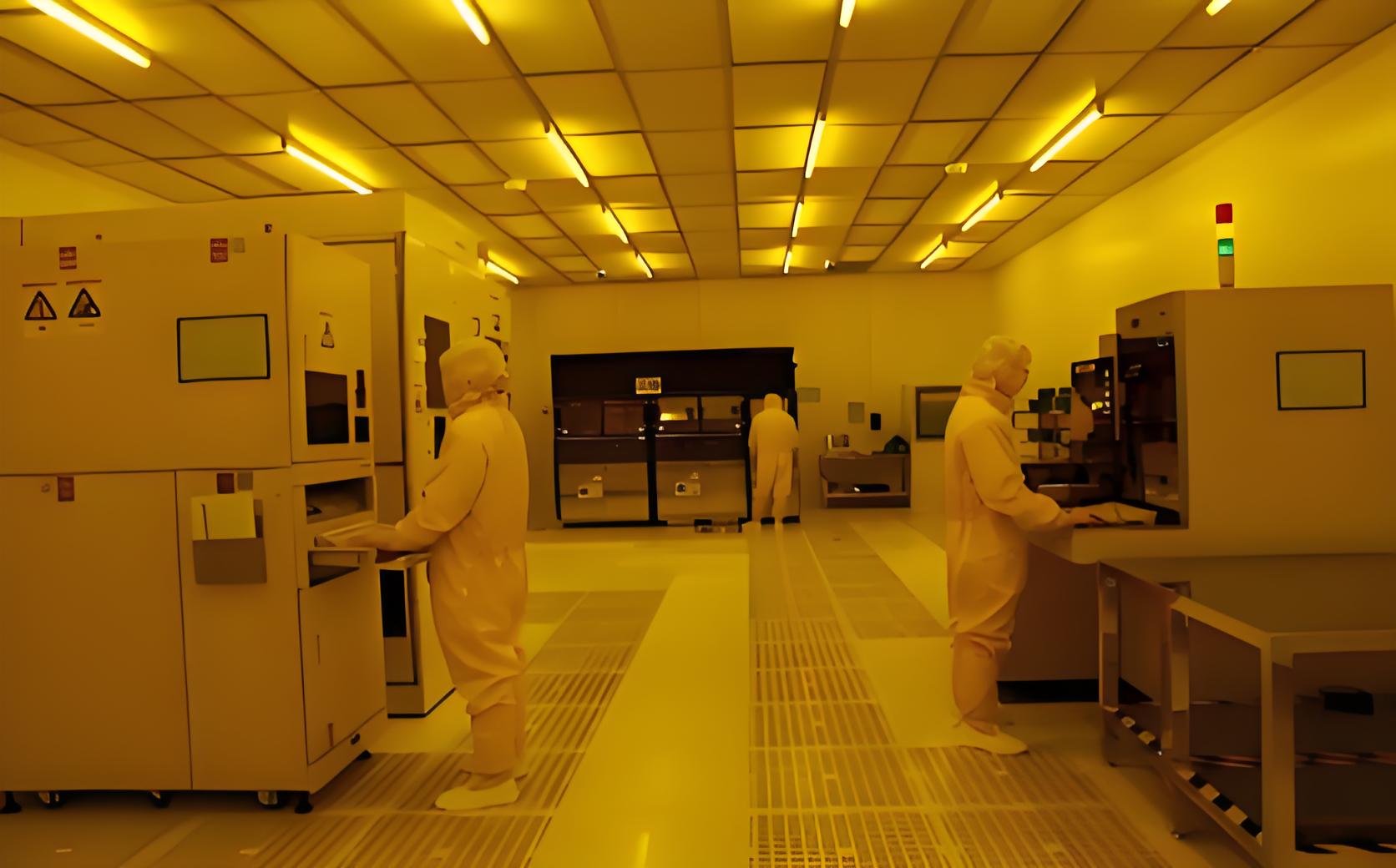

In industries where a single speck of dust can ruin a microchip or a stray microbe can compromise a vaccine, the production environment itself becomes a critical component. This is where the specialized discipline of cleanroom engineering comes into play. It moves beyond simple room construction to encompass the complete technical planning, integration, and validation of a controlled environment.

Cleanroom engineering is the multifaceted practice of creating spaces where environmental parameters are precisely regulated. This includes the concentration of airborne particles, temperature, humidity, air pressure, and airflow patterns. It's a fusion of architectural design, mechanical engineering, physics, and stringent protocol development.

The goal is not just to build a room, but to engineer a reliable, repeatable, and certifiable ecosystem for sensitive processes. From semiconductor fabs and pharmaceutical sterile fill lines to advanced aerospace assembly, successful cleanroom engineering is the unseen backbone of quality and yield.

Every successful project begins long before the first wall panel is installed. The initial planning phase is arguably the most critical in cleanroom engineering.

This involves defining the clear objective. What ISO classification is required? What specific processes will occur inside? How many personnel will be present? Engineers and clients must also map out material and personnel flows meticulously.

They assess the impact on utilities like power, water, and gases. A thorough feasibility study examines the existing building's constraints—ceilings heights, floor loads, and existing HVAC capacity. Skipping this detailed front-end planning is a common pitfall that leads to cost overruns and performance shortfalls.

The heating, ventilation, and air conditioning system is the beating heart of any cleanroom. Its design is a central pillar of cleanroom engineering.

This system has a singular, demanding job: to continuously flush out internally generated contaminants. It achieves this through a combination of high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) or ultra-low penetration air (ULPA) filtration and carefully calculated air change rates.

The airflow strategy—whether turbulent, unidirectional, or a hybrid—is selected based on the cleanliness class. Pressure differentials are engineered to cascade from the cleanest area to the less clean, ensuring air flows outward, not inward. Temperature and humidity control must be exceptionally stable, often within a ±1°C range.

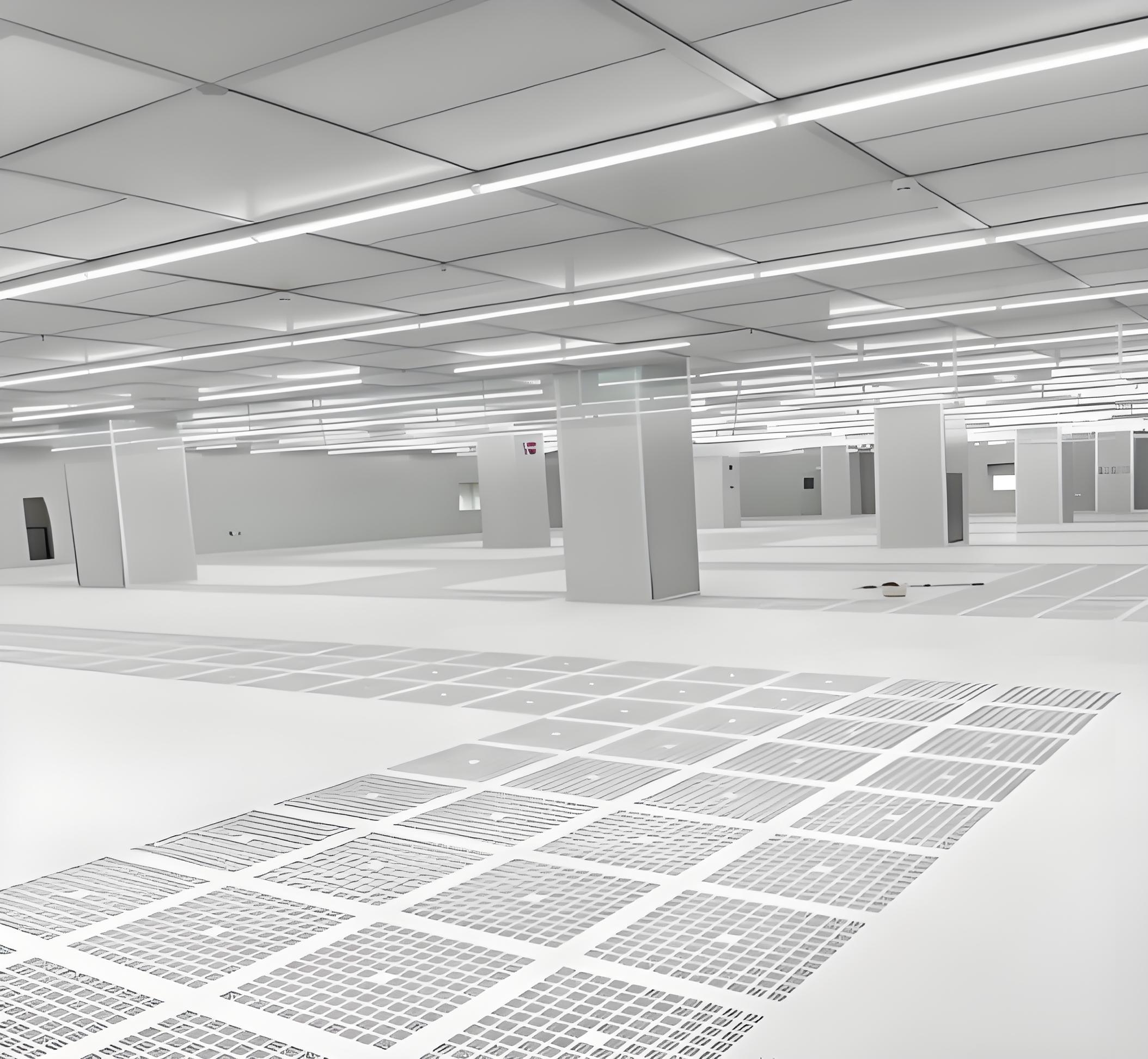

The shell of the cleanroom must support the performance of the HVAC system. Walls, ceilings, and floors are selected for their cleanability, durability, and non-shedding properties.

Modern projects often utilize modular cleanroom systems. Pre-fabricated wall panels with insulated cores offer excellent thermal properties and fast installation. Seamless, coved flooring systems like epoxy or urethane prevent particle traps. Every material, from sealants to door finishes, is chosen based on its contribution to the clean environment.

Lighting is another key consideration. Fixtures must be sealed, smooth, and designed to minimize airflow disruption. They must also provide ample, shadow-free illumination for delicate tasks without generating excessive heat.

Advanced engineering also focuses on minimizing contamination generation within the space. This involves designing ergonomic and functional gowning rooms with proper airlocks.

Material transfer is managed through pass-through chambers, sometimes with integrated sanitization like UV-C light. For the highest grades, equipment may be placed outside the main clean zone, with only process tools extending inside.

The selection of furniture and tools is also part of the engineering scope. Stainless steel workstations with smooth edges, dedicated cleanroom wipers, and specialized vacuums are all specified to maintain integrity.

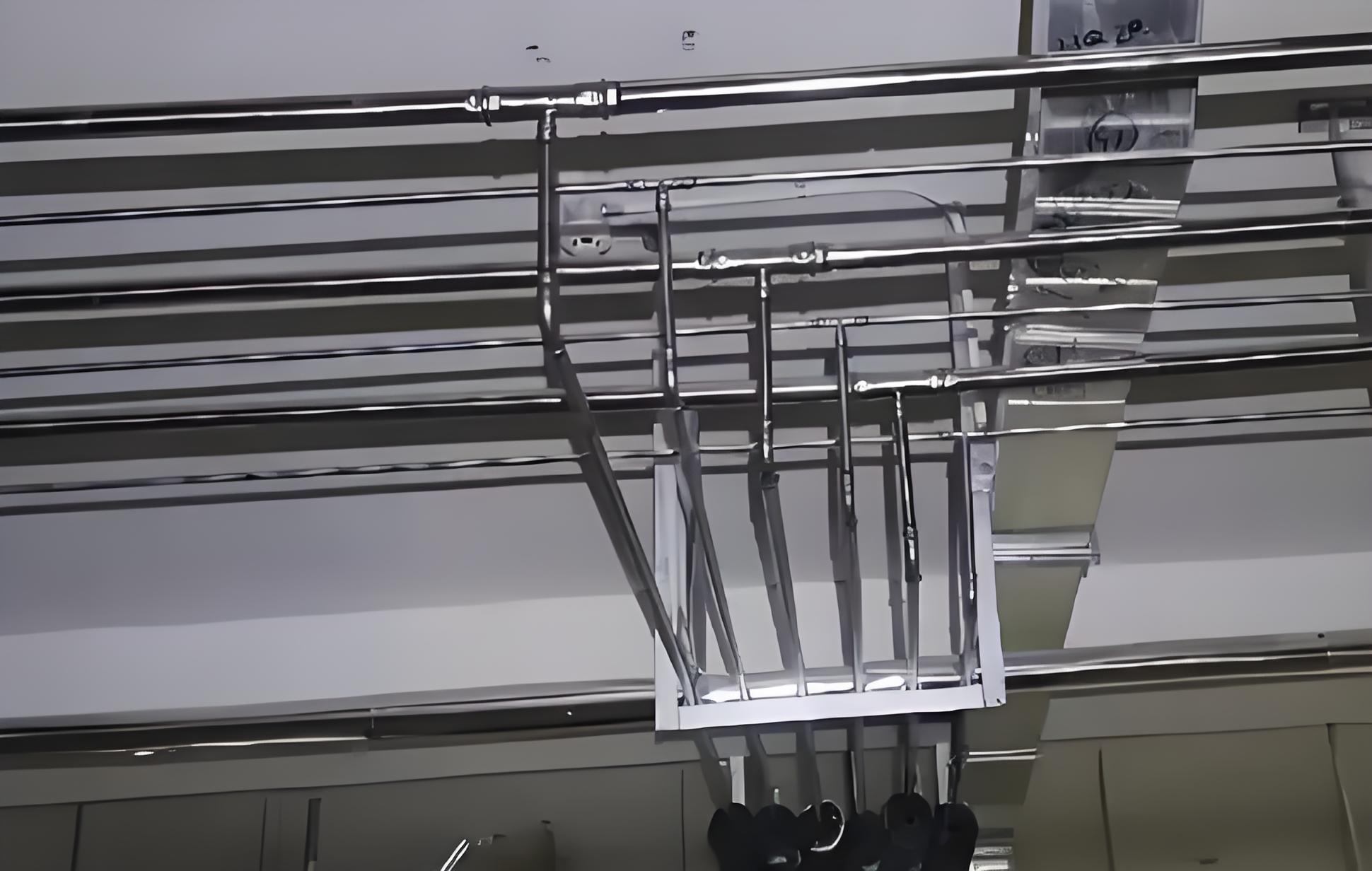

A cleanroom is rarely just an empty space. It houses production equipment with specific needs. Integrating these utilities cleanly is a complex task.

Process cooling water, compressed dry air, nitrogen lines, solvent exhaust, and electrical raceways must be routed without creating crevices or shelves that collect dust. Service chases and interstitial spaces above the ceiling grid are often engineered to allow maintenance access without breaching the main production area.

For regulated industries like pharmaceuticals and medical devices, the engineering process extends into qualification. This is the formal proof that the facility performs as intended.

The cleanroom engineering team typically supports the client through this rigorous process. It includes Installation Qualification (verifying equipment is installed correctly), Operational Qualification (proving systems operate to specifications), and Performance Qualification (demonstrating the room consistently meets its classification under simulated use).

Data from particle counters, pressure sensors, and microbial samplers is collected and analyzed. This creates the documented evidence required for regulatory submissions.

Given this complexity, engaging a specialist firm from the outset is a strategic advantage. A partner like TAI JIE ER brings cross-industry experience to the table. They understand how to balance theoretical standards with practical, operational reality.

Their role is to translate a client's process requirements into a fully integrated, compliant, and efficient facility. They manage the interplay between architectural, mechanical, electrical, and control systems. This holistic oversight prevents costly conflicts during construction and ensures a smoother path to operational readiness.

Modern cleanroom engineering must also consider energy efficiency and adaptability. These facilities are significant energy consumers, primarily due to the HVAC system.

Engineers now employ strategies like variable air volume controls, heat recovery wheels, and optimizing room pressurization to reduce the carbon footprint and operational cost. Designing for flexibility—with modular walls and scalable utility grids—allows spaces to adapt to future process changes without a complete rebuild.

Cleanroom engineering is a dynamic field. It demands a systematic, detail-oriented approach to create environments where the air itself becomes a controlled raw material. It’s the essential discipline that allows science and manufacturing to push the boundaries of what's possible, one clean cubic meter of air at a time.

Q1: What's the main difference between a "cleanroom" and a "controlled environment"?

A1: While often used interchangeably, a "cleanroom" specifically refers to a room with a controlled particle count per ISO standards. A "controlled environment" is a broader term that can include rooms controlling for other factors like temperature, humidity, or static, without necessarily achieving a formal ISO particle classification.

Q2: How critical is the facility's location to the cleanroom engineering process?

A2: It's highly critical. An existing building's structural capacity, ceiling height, and location of external walls significantly influence design. Proximity to vibration sources (like railways) or areas with high outdoor pollution can add complexity and cost to the filtration and structural isolation systems needed.

Q3: Can you upgrade an existing cleanroom to a higher ISO class?

A3: It is possible, but it often requires major modifications. Upgrading typically means increasing air change rates, installing higher-grade filtration (e.g., moving from HEPA to ULPA), potentially replacing the entire air handling unit, and improving room seals and materials. A feasibility study by a cleanroom engineering firm is essential first.

Q4: Who is responsible for the ongoing performance monitoring of a cleanroom?

A4: Ultimately, the facility owner/operator is responsible. However, a strong cleanroom engineering partner will deliver a system designed for easy monitoring, with clear access points for sensors and a Building Management System (BMS) for data collection. They also provide the initial performance baseline and often offer ongoing service contracts.

Q5: Why is pressurization so important in cleanroom design?

A5: Maintaining a positive or negative pressure differential between adjacent areas is a primary containment strategy. Positive pressure keeps contaminants from entering a clean space. Negative pressure is used in hazardous areas (like some pharmacy compounding rooms) to keep contaminants inside. It’s a fundamental engineering control for directional airflow.